Severe hailstorms can cause extensive economic damage to both crops and properties. Report by Munich RE shows that damage of individual events can exceed billions of dollars as the risk has increased in the past decades. Hail damage to properties, such as cars, roofs and windows, becomes substantial when the diameter of hailstones approaches and exceeds 5 cm. Each year there are a number of such events when hail of this size occurs across Europe and this year, 2018, was no exception.

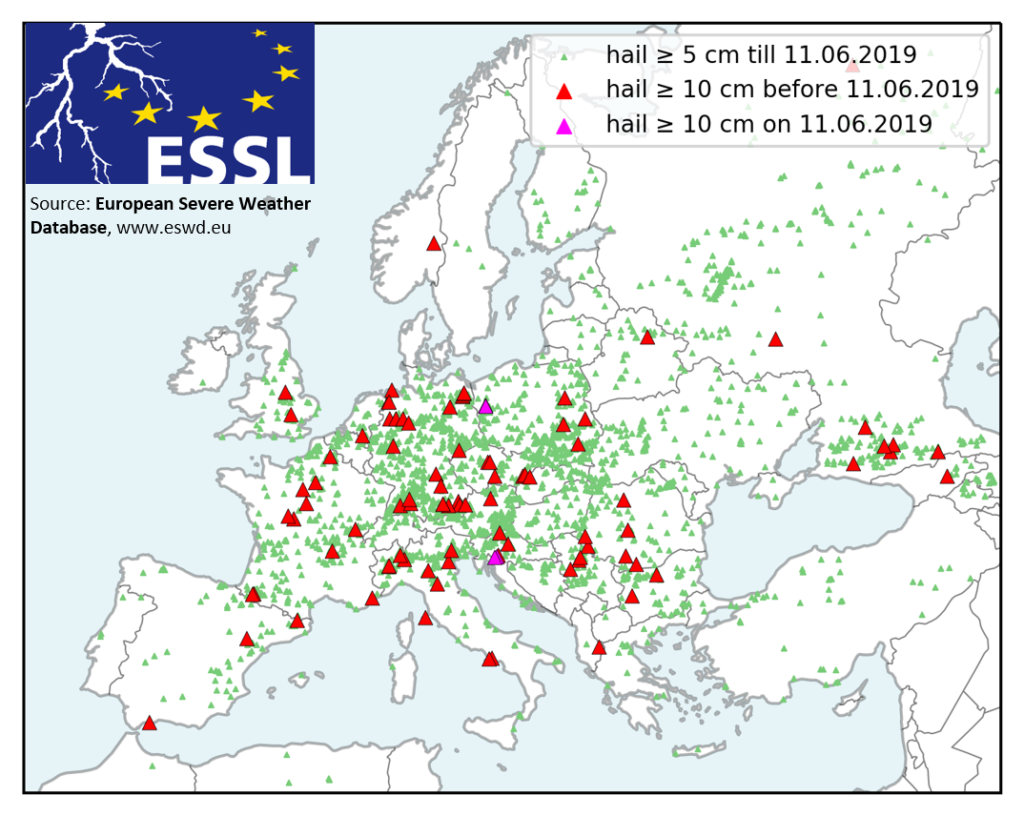

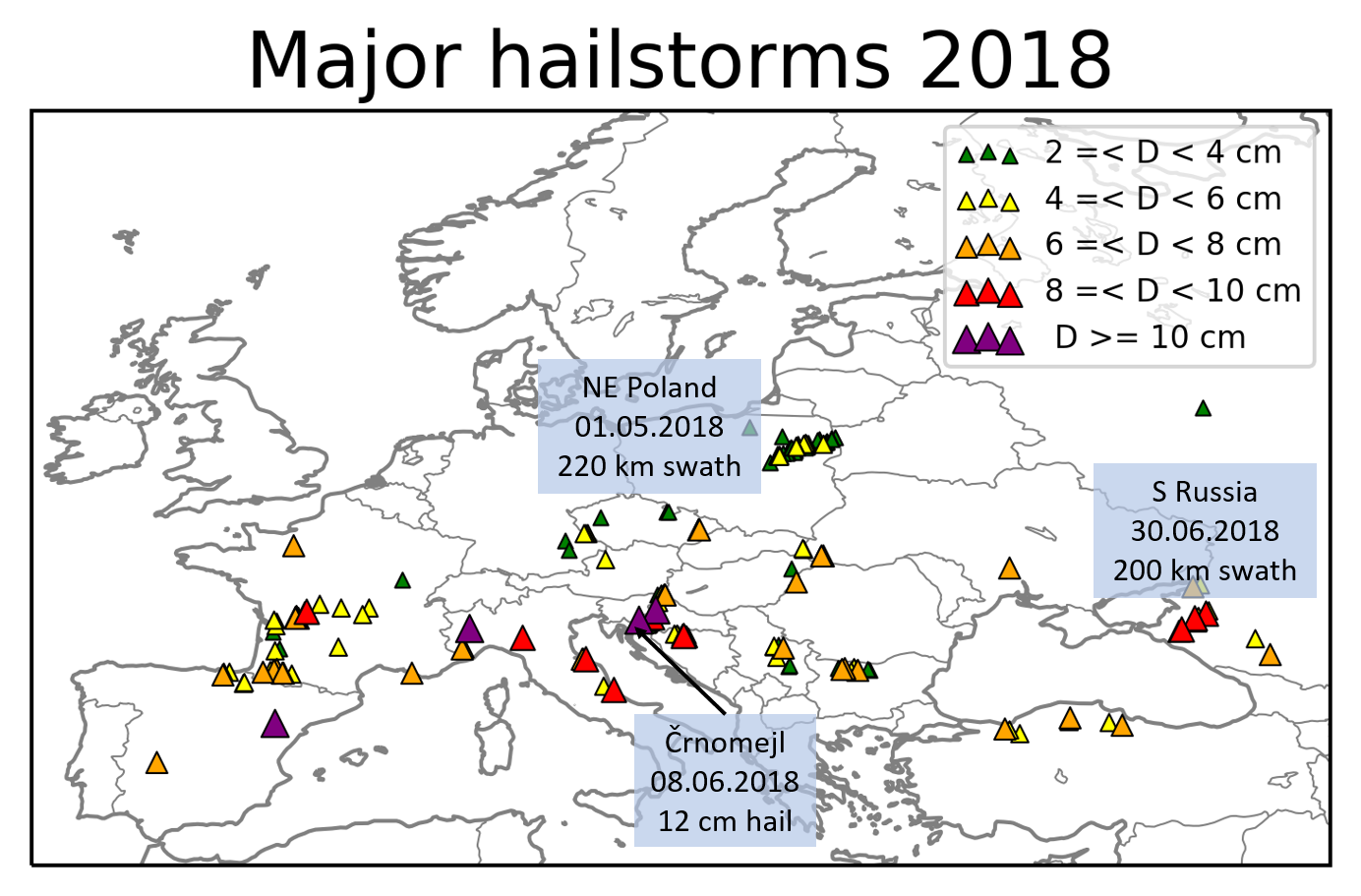

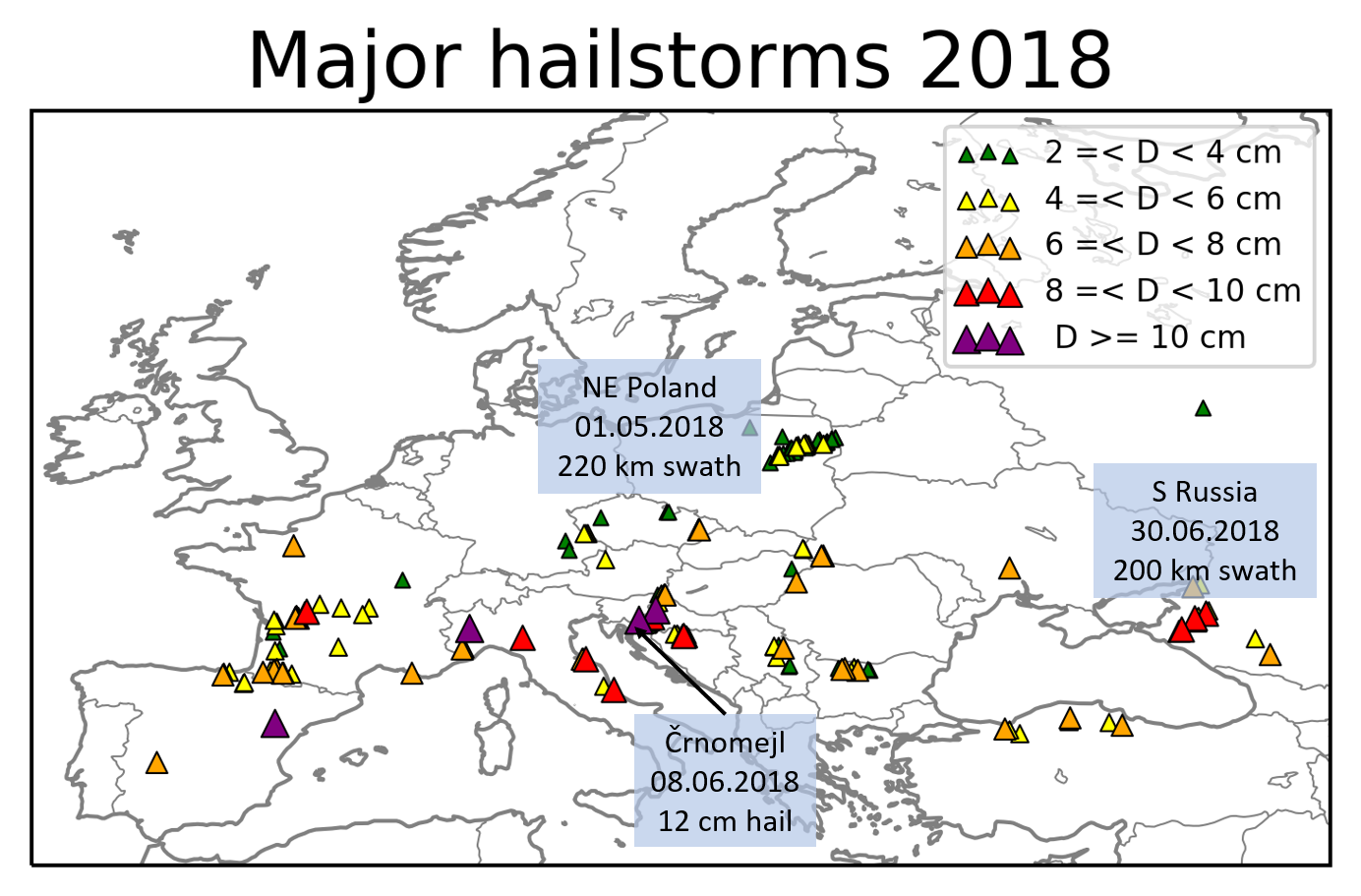

By looking at the ESWD dataset, we found 26 days, when hail exceeded 5 cm and caused significant damage to the properties. The spatial distributions of these major hail events and associated hail sizes can be found in in Fig. 1. The largest hail size was observed on 8 June 2018, when the town of Črnomelj, Slovenia was hit by giant hail up to 12 cm in diameter, destroying hundreds of roofs and cars. The hail swath on that day (40 km) was much shorter compared to long-lived hailstorms of 1 May in Poland (220 km) or the hailstorm of 30 June in southern Russia (200 km).

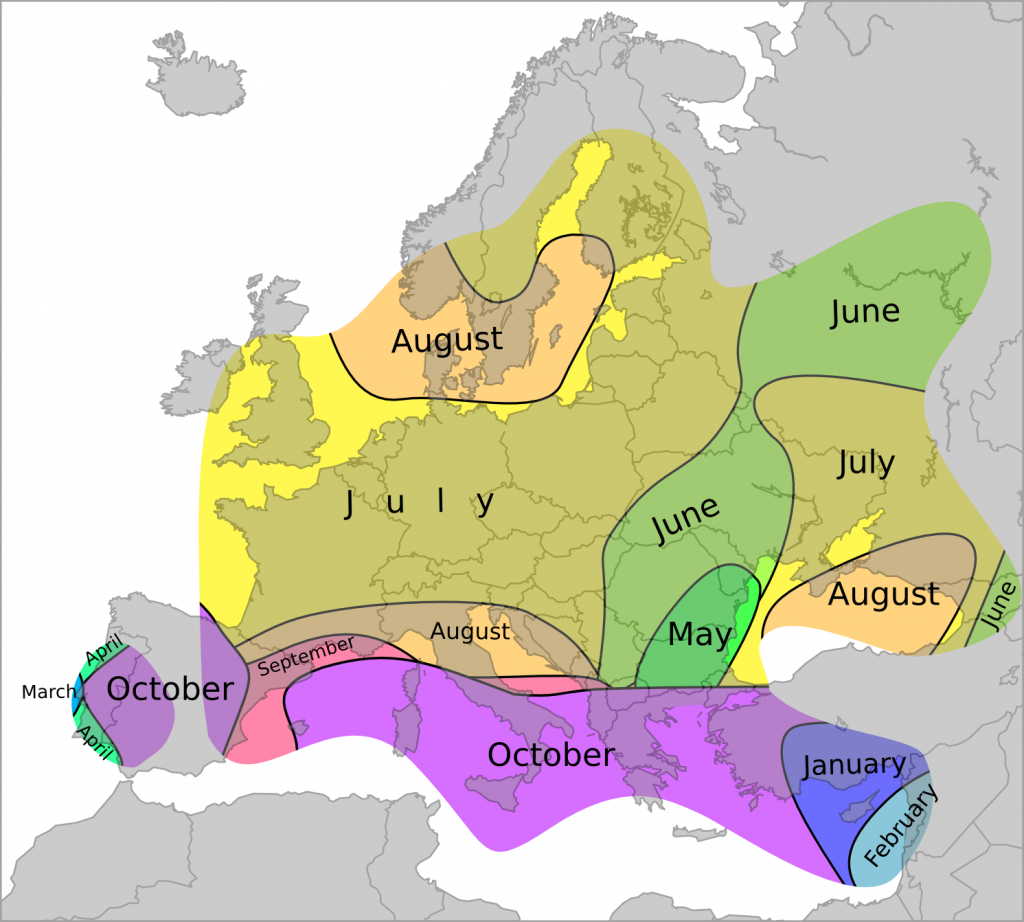

Fig. 1. Severe hail reports associated with 26 damaging hailstorm events over Europe in 2018. Size and colour of the symbol represent the observed hail size.

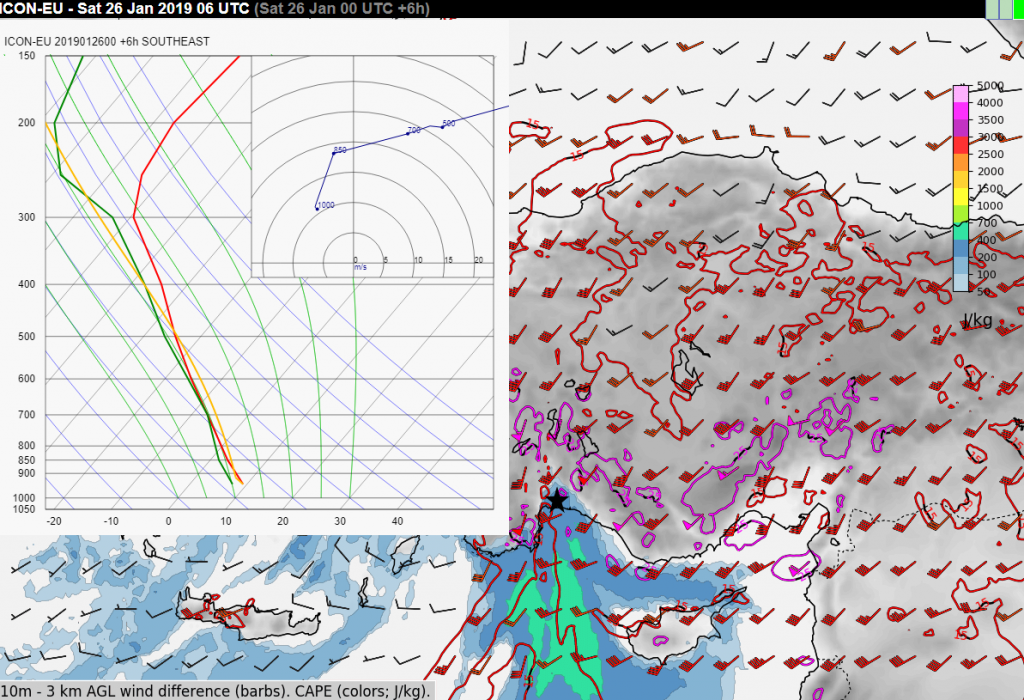

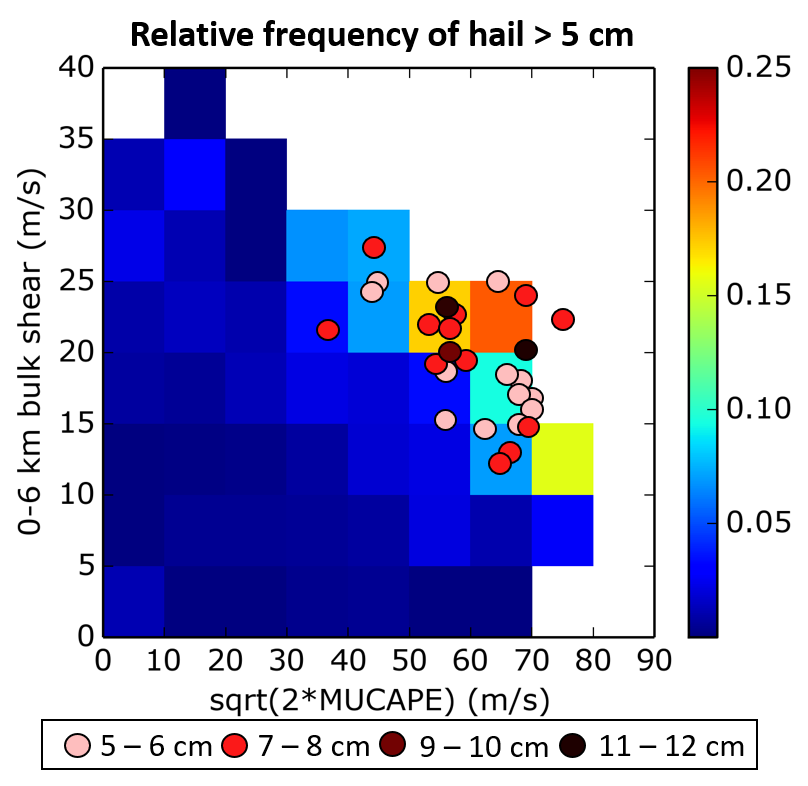

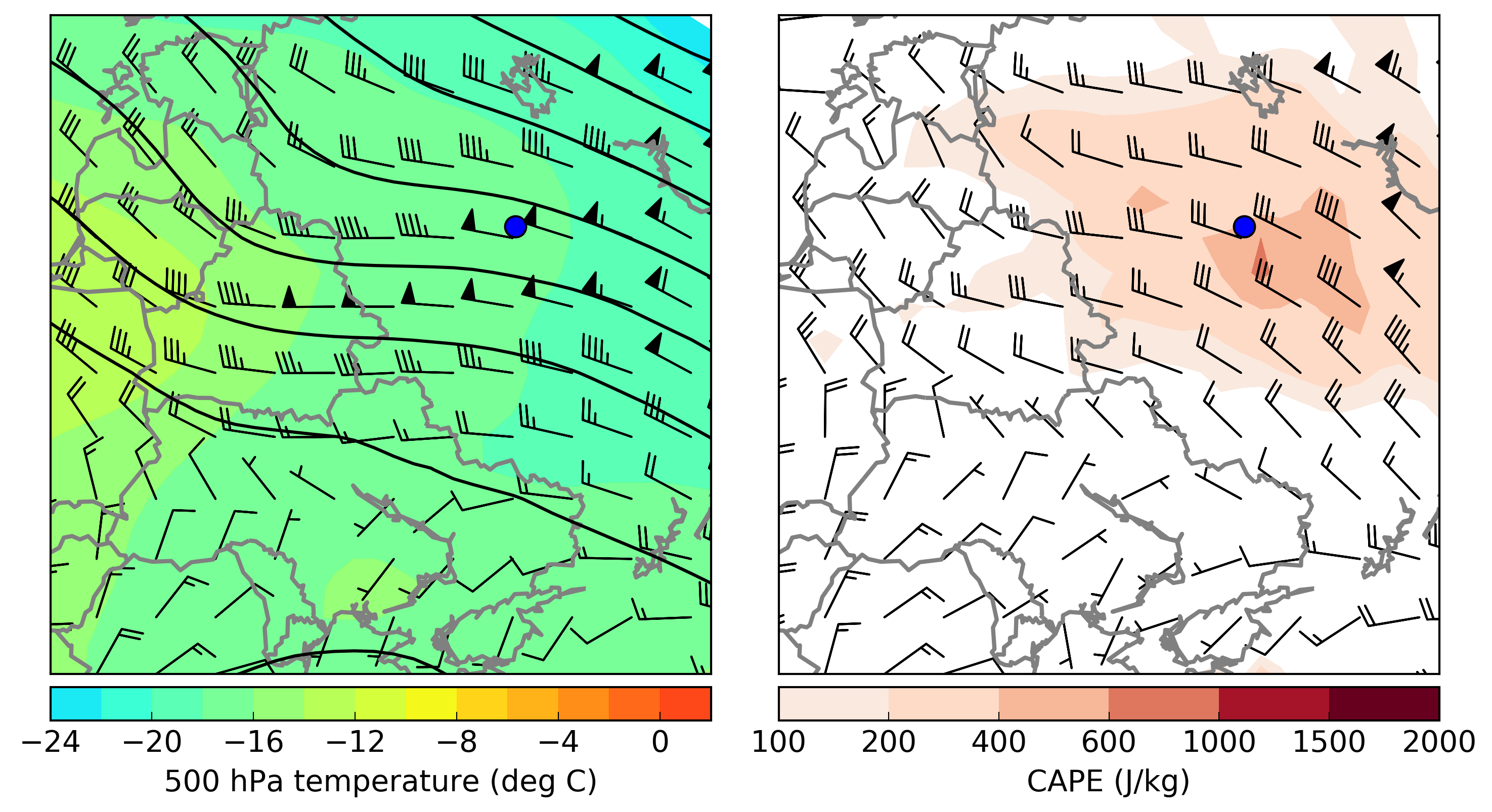

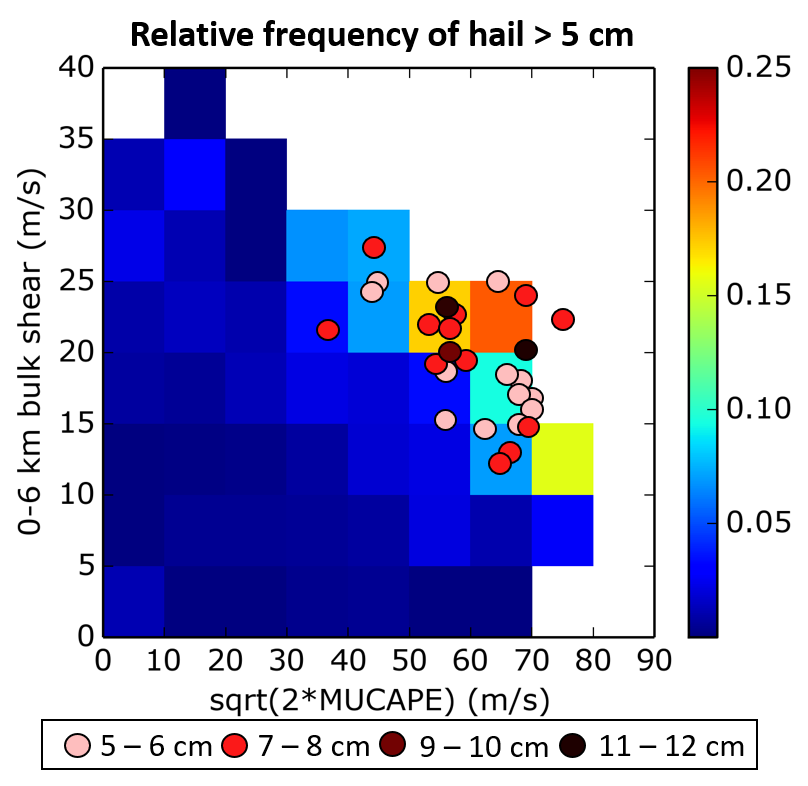

These damaging hailstorms occurred in an environment of moderate to high CAPE and bulk 0–6 km wind shear exceeding 15 m/s, conditions which favour strong updrafts and well-organized convection, including supercells. Our research shows that such conditions may become more frequent in the future. As we compare with the sounding database developed by Pucik et al (2015), most of these events occurred in typical conditions for damaging hailstorms (Fig. 2). Several of these events formed in rather weak vertical wind shear (i.e., bulk 0-6 km shear ranging from 10 to 15 m/s) but these cases were confined to the proximity of complex orography, where shear could be strongly enhanced locally.

Fig. 2. Environments of damaging hailstorms over Europe in 2018 (dots) compared to the relative frequency of hail > 5 cm (colour bar) as a function of CAPE and 0-6 km bulk shear based on Pucik et al (2015). Colour of dots represents the maximum observed hail diameter with each event.

Description of individual events

01.05.2018 (Poland). An isolated supercell cut a 220 km long hailswath across the regions of Mazowieckie and Podlaskie in northeastern Poland with hail up to 5 cm in diameter.

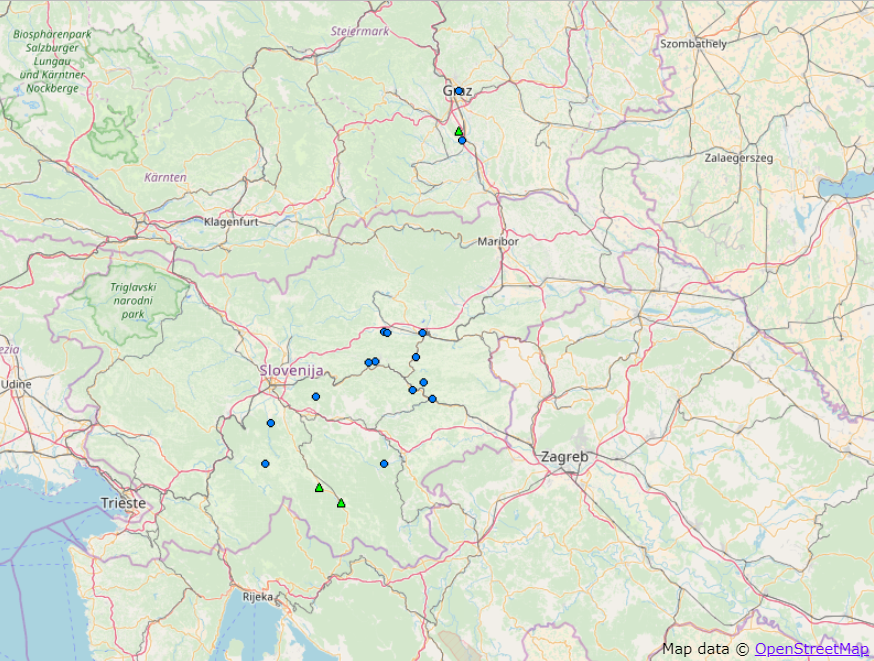

02.05.2018 (Slovenia). Very large hail was recorded in the districts of Lendava, Murska Sobota, Gornja Radgona and Ljutomer in northeastern Slovenia, with hailstones up to 6 cm in diameter. Hail damaged cars and roofs.

15.05.2018 (Bulgaria). Very large hail hit several villages and towns within a 120 km long path tracking through the districts of Vraza and Pleven in northwestern Bulgaria with hailstones up to 7 cm in diameter. Extensive damage to cars and trees was reported from the town of Pleven.

24.05.2018 (Spain). Hailstorm hit the town of Garciaz in Extremadura province, southwestern Spain, with hailstones up to 7 cm in diameter. Cars, roofs and fruit plantations were damaged by the storm.

26.05.2018 (France and Italy). Violent thunderstorms hit the regions of Aquitaine and Poitou-Charentes in southwestern France with a 100 km long hailswath originating near Bordeaux and devastating vineyards in the area. Hail up to 6 cm in diameter was reported. On the same day, very large hail, up to 7 cm in diameter was also reported from Piemonte province, northwestern Italy.

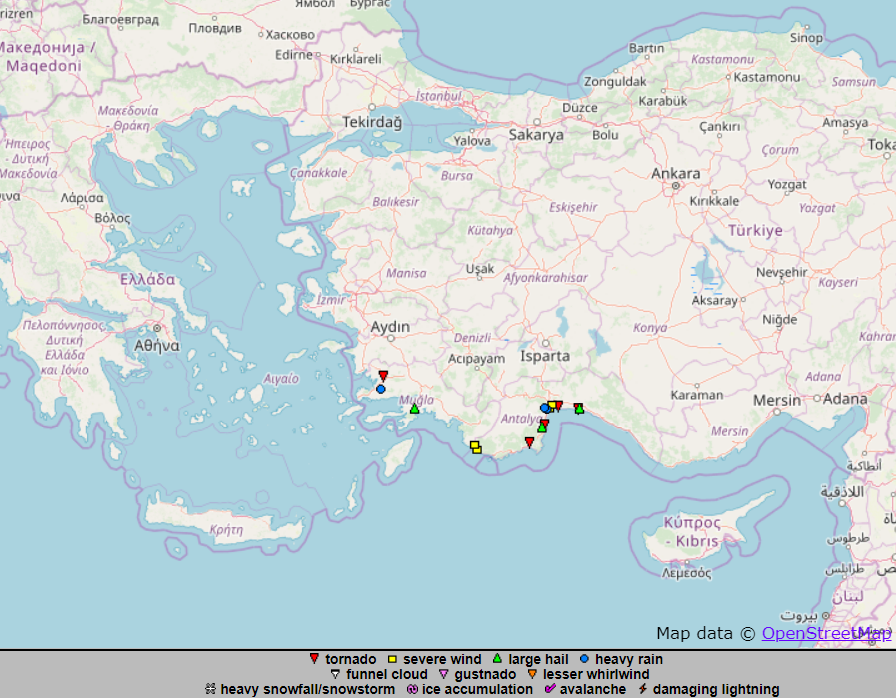

27.05.2018 (Turkey). Severe hailstorms hit Samsun province, northern Turkey. Six people were injured in Muratbeyli village as 6 cm large hailstones smashed car rear windows and roof tiles.

04.06.2018 (Italy). A right-moving supercell brought violent hailstorm to the town of Noceto in Emilia-Romagna province, northern Italy. Very large hail up to 8 cm in diameter damaged cars.

08.06.2018 (Slovenia and Croatia). Two very severe hailstorms occurred in Slovenia and Croatia. The town of Črnomelj in southern Slovenia was particularly hit as supercell produced hail up to 12 cm in diameter. Hundreds of cars, roofs and solar panels were seriously damaged. Another supercell hit the districts of Karlovačka, Zagrebačka and Krapinsko-Zagorska in central and northern Croatia. Hail up to 10 cm in diameter hit Grabovec town, damaging cars.

11.6.2018 (Germany and Czech Republic). Violent, wind-driven hailstorm from supercell damaged roofs, facades and windows in Furth im Wald town in Bayern state, southeastern Germany, and along the Czech-German border. Hail up to 6 cm in diameter was observed.

12.6.2018 (Ukraine). Supercells produced very large hail over Uzhhorod town and Irshava district in Zakarpatska province, southwestern Ukraine. Car rear windows and roof tiles were smashed by hailstones up to 6cm in diameter. On the same day, a violent hailstorm hit villages in the northern parts of Bihor County in western Romania. Hodoš village was worst hit by hailstones up to 6cm in diameter, destroying roof tiles.

13.6.2018 (Serbia). Supercell produced wind-driven hail with diameter up to 6 cm over central and east Serbia. Extensive damage to crops, windows, roofs, cars and facades of houses was observed.

26.06.2018 (Turkey). Violent hailstorm with hail up to 6 cm in diameter caused damage in Düzce province, northwestern Turkey.

28.06.2018 (Ukraine). A violent hailstorm hit areas in Mykolayivska province, southern Ukraine. Hailstones up to 6 cm in diameter caused extensive damage in Yuzhnoukrainsk town.

30.6.2018 (Russia). An isolated, long-lived supercell produced more than 200 km long hail swath with hail up to 8 cm in diameter in the districts of Krasnoarmeyskiy, Timashevsk, Bryukhovetskaya and Pavlovskaya in Krasnodar Region, southern Russia. Novokorsunskaya town was worst hit by very large hail which caused extensive damage to crops, cars, car windshields, roofs and windows. Additionally, very large hail up to 6 cm in diameter also caused extensive damage to cars and houses in Pavlo-Ochakovo area, Rostov province.

01.07.2018 (Russia). A violent hailstorm hit Stavropol region, southern Russia. Hail up to 7 cm in diameter hit the local areas of Bekeshevskaya town.

04.07.2018 (France). Several hailstorms produced very large hail up to 8 cm in diameter over France. 11 people were injured in the Poitou-Charentes region village of Saint-Sornin, where 7 cm hail produced extensive damage to roofs. Houses in villages south of La Rochefoucauld town were badly damaged and rendered uninhabitable by water damage following the very large hail. In Aquitaine region, southwestern France, very large hail up to 6 cm in diameter caused significant damage in some places east of Pau city.

14.07.2018 (Italy). A severe hailstorm hit Piemonte province, northwestern Italy. The town of Chivasso was hit by giant hail up to 10 cm in diameter. Cars and roofs were damaged during the hailstorm.

16.07.2018 (Italy). Several instances of very large hail, up to 8 cm, were reported from Marche province, eastern Italy. Hail caused extensive damage to cars in the town of Pesaro and surrounding villages.

21.07.2018 (Bosnia and Herzegovina). Very large hail up to 8 cm reported from Srpska territory, northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. 1 person was injured by 6 cm large hail in Prijakovci village, north of the city of Banja Luka. Roofs and cars were damaged by the storms in several villages.

24.07.2018 (Turkey). A strong hailstorm hit parts of Kastamonu province in northern Turkey causing extensive damage to cars and houses in Kuzyaka and Seyh villages by hailstones of at least 5 cm in diameter.

05.08.2018 (Czech Republic). Very large hail up to 6 cm was reported from villages in Zlín and Olomouc regions, eastern Czech Republic. Cars and roofs damaged by the hail.

07.08.2018 (France). Very large hail up to 6 cm (weighing 150 g) was reported in Basse-Normandie region, northern France. Roofs, cars and vegetation were damaged.

09.08.2018 (France). Very large hail up to 7 cm fell over Marseille city and Aubagne town, southern France.

28.08.2018 (Spain). Very large hail up to 7 cm in diameter was observed in Euskadi region, northern Spain.

02.09.2018 (Italy). Very large hail up to 8 cm was reported from Abruzzo province, eastern Italy with extensive damage to cars and roofs.

05.09.2018 (Spain). A severe hailstorm hit Albalate del Arzobispo town in Aragón province, northeastern Spain with giant hail up to 11 cm in diameter causing damage to roofs and cars.

13.09.2018 (Turkey). Severe hailstorm with hail up to 6 cm in diameter hit Kastamonu city in northern Turkey. Extensive damage was inflicted to cars and houses.